In collaboration with master’s students at the Media Software Design programme, researchers in the Living Archives project initiated an exploratory study aiming at supporting urban gardening practices through digital technologies. The study resulted in two prototypes: the Sensor Stick generating data on moisture levels at various soil depths, and the Voice Garden enabling gardeners to share ’local’ knowledge.

Living Archives – Urban Archives

Living Archives is a four-year long multidisciplinary research project that among other things analyzes and prototypes how digital archives and open data can become a meaningful resource to specific communities of practice. The Urban Archiving theme, which the project presented in the following is part of, explores archival practices in relation to urban sustainable development. The project involved media software design students and a group of urban gardeners that in an iterative design process, based on principles of participatory design, explored how digital technologies generating open data and archive material can become social resources that support and stimulate activities in the field of urban gardening.

Urban gardening

The practices of urban gardening, also called urban agriculture, urban farming, and community farming are not new (Dziedzic & Zott, 2012; Jimenez, 2009). They have been a part of human history since the start of urbanisation. When the industrialisation decreased the ability to produce food close to or within the city, urban people became dependent on food supply and production in rural regions miles away (Gorgolewski et al., 2011). This organisation of mass food production has become a necessity in today’s world. But, what happens if the global food industry collapses and food becomes inaccessible? According to the United Nations, 66 % of the world’s population will by the year of 2050 be living in urban areas (ESA). The UN climate report 2014 (IPCC 2014) put an emphasis on the vulnerability of food supply, and call for alternative actions to ensure food security. It is also claimed that the separation between cities and food sources is directly linked to many of the big problems of today, such as climate change, obesity, pollution, hunger and poverty (Gorgolewski et al., 2011). In response to these emerging circumstances, many cities around the world have taken action, and started to plan for food production sites, and actions to support urban gardening. Urban gardening is talked about as a strategic and infrastructural action, and cities are increasingly viewed upon as places for food production (Gorgolewski et al., 2011).

Along with strategies for human survival (including food supply as well as climate change), social matters and lifestyle trends have been driving forces behind the urban gardening movement (Jimenez 2009, Wiman 2014). Gardening has become a means to reconnect to and understand the many aspects of food that have been lost in the urbanisation process; for example, how food grows, what crops grow best given the local conditions, and how to harvest. These aspects are part of urban citizens becoming better informed as consumers, and gain a greater appreciation for food, and where it comes from.

The exploratory study: new digital technologies, open data, and digital archives in urban gardening contexts

In collaboration with master’s students at the Media Software Design programme at Malmö University, we initiated a project aiming at exploring potentials of new digital technologies to generate open data and archive materials that support and stimulate urban gardening practices. The design brief given to the students was: Explore how sensors kits/open hardware generating/accessing open data can support urban gardening practices.

The procedure: methods, context, process

The design process driven by the students followed a participatory design approach (see for example Björgvinsson et al. 2010; Simonsen & Robertson 2013). In short it can be described as a diverse collection of principles and practices aimed at making technologies, tools, environments, businesses, and social institutions more responsive to human needs, inherently also including aspects of sustainable development. One of the central principles of participatory design is the direct involvement of the users. Such co-design processes often take form of iterative experiments providing a toolbox of different practical techniques to engage the users, for example methods for doing mock-ups, rapid prototypes, interviews, as well as ethnographically inspired studies of the practices.

The stakeholders and collaborators that the students were working with in this project were four urban gardeners doing gardening work as a hobby, for food production, and for growing flowers and herbs. Three of the gardeners had allotments in public community gardens, and one had his own backyard garden.

The students invited the four gardeners to participate in four design workshops. Two workshops took place in a greenhouse in a public community garden, and two at the university.

Figure 2. The iterative design process. The stars symbolise the design workshops, the circles are sessions where teachers and students met, and the squares are deliverables (sketches, prototypes, papers etc.).

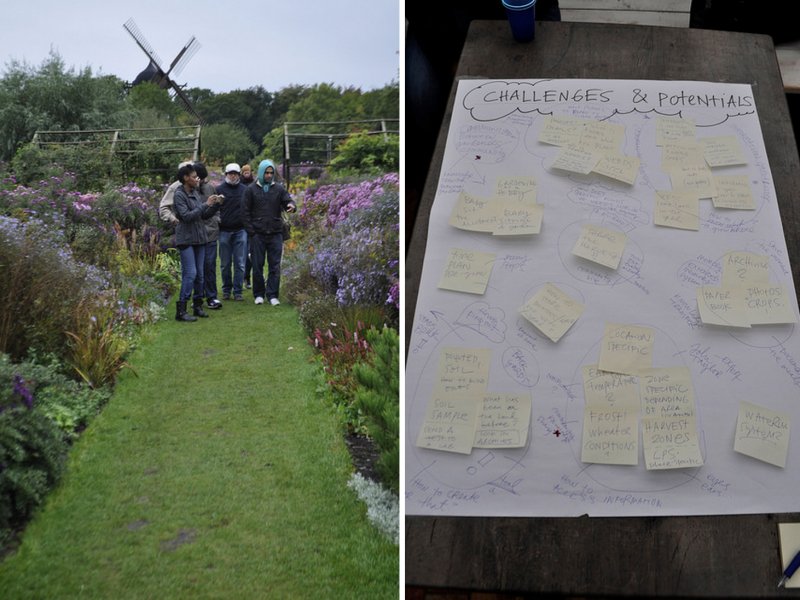

The first workshop was dedicated to mapping gardening practices over a year, and for establishing a relationship between the students and the gardeners. A year (January-December) in the form of a circle was drawn on a large piece of paper and placed on a table that the participants gathered around. In the first round of discussion, the gardeners were asked to describe a year in terms of gardening activities. The information obtained were categorised into five categories: Action, Tool, Information, Physical material, and People. The students wrote down the information on post-it notes in different colours, one color per category, and placed them on the paper with the circle. In the second round the students asked the gardeners to fill the “gaps” in the gardeners’ stories, and asked about issues that they had not understood. Step by step an image of a year of gardening activities emerged.

Based on the discussion and information gathered, a list of challenges and potentials emerged. This list served as a basis for the next step in the design process, that is, conceptual discovery, to identify what problem to work with, and to formulate the scope and aim of the design concept.

Figures 5 and 6. Students and gardeners taking a walk through the garden. The list of challenges and potentials CC:BY-NC.

At the three following workshops, the students’ design concepts were presented to the gardeners, and iterated by using various methods of rapid-prototyping exercises. The concepts were tested, evaluated and re-designed.

More photos from the workshops.

Two prototypes: Sensor Stick and the Voice Garden

The outcome of the design process is two prototypes briefly described in the following text, and more in detail in the posters, and in papers written by the students.

The first prototype is the Sensor Stick, a tool that generates data from the soil, which is designed to help gardeners to measure the moisture level at various soil depths (2 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm). The idea is that the sensor stick, combined with an Android-based application, will assist the gardener in providing the correct amount of water for the plants. It also indicates the ultimate moisture conditions for a seed or bulb. The next step is to enable storing of the collected data in a database, which would serve as an archive of open climate data that can be shared with other gardeners.

For a more detailed description of the concept, see the Sensor Stick poster and Sensor Stick paper.

Students that developed the concept: Salle Dhali, Fanny Ericsson, Lorand Fekete, and Tulasi Surapaneni.

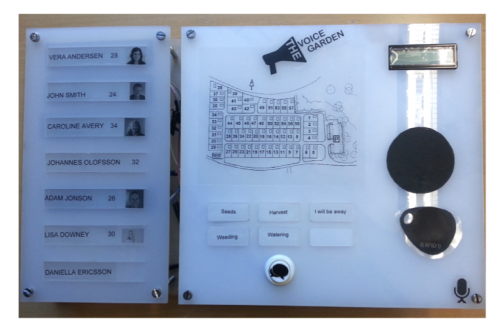

The second prototype, the Voice Garden, is an interactive billboard and a smartphone app. The aim is to explore how digital technology can contribute to strengthen the gardening community by bridging the local communication gap between the gardeners. Via a billboard and/or a smartphone app, the gardeners can send and receive audio messages privately, or as public announcements, within their local urban-gardening community. To bridge the gap between gardeners who are smartphone users, and gardeners who are non-smartphone users, two interfaces are offered: the billboard and the app. Some of the data (for example a counter of visitors), generated by the gardeners is visualised on the billboard and is accessible to the public. Data such as the private messages sent from one gardener to another is stored in the personal archive of the gardener.

Figures 11 and 12. Prototypes of the interactive billboard and the app.

For a more detailed description of the concept, see the Voice Garden poster and Voice Garden paper.

Students that developed the concept: Bibi Asma, Skander Hamada, Emma Mainza Chilufya, and Jennifer Meurling.

Living archives – urban archives – open data and archives in urban gardening contexts?

The Sensor Stick and the Voice Garden are two early examples of how digital technologies could be applied to generate, access, and store various kinds of data that support and stimulate practices of urban gardening. The concepts are still in an early phase of development, and there are many potentials left to be explored. For example, how could the generated data be made accessible to the public and thus serve as an open data source that potentially could be applied in a larger context of urban sustainable development? Another interesting aspect to further study is the topic of inclusion, which one of the student groups addressed by designing two alternative interfaces to access the data generated: the interactive billboard and the app. When discussing open data, we need to address issues of accessibility and different levels of digital literacy among the potential users.

The iterative design process run by the students also serve as a concrete example of how a participatory approach, manifested through a co-design process, can be used to identify relevant challenges to tackle in an, for the participants, unknown field. None of the students had any prior experience of urban gardening, nor had the gardeners any experience of developing digital technologies. Together and in dialogue, the two concepts were developed, designed, and re-designed.

The experiences gained in this exploratory study serve as valuable input in the research theme Urban Archiving. The research theme has a focus on archival practices in urban planning by exploring questions such as: What is an archive in the context of urban planning, and how can open data sets become meaningful resources in urban development? The work by the students, and the two prototypes presented, provide important input to this on-going discussion.

Acknowledgements

Students: Bibi Asma, Salle Dhali, Fanny Ericsson, Lorand Fekete, Skander Hamada,Emma Mainza Chilufya, Jennifer Meurling, and Tulasi Surapaneni. Teachers: Daniel Spikol, and Patrik Ferander. Gardeners: Julia Boström, Maja, Rune Jönsson, and Christina Worsch.

References

Björgvinsson, Erling, Ehn, Pelle and Per-Anders Hillgren (2010). ‘Participatory design and democratizing innovation’, Participatory Design Conference, Sydney.

Dziedzic, Nancy and Zott M., Lynn (2012). Urban Agriculture, Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press.

Gorgolewski, Mark; Komisar, June; and Nasr, Joe (2011). Carrot City : Creating Places for Urban Agriculture. New York: The Monacelli Press, Random House Inc.

ESA (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division) (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352). New York: United Nations.

Jimenez, Johanna G. (2009). Staden som åkermark : Stadsodling i Malmö och New York. Malmö: Eklundhpaglert Förlag.

Halse, Joachim, Brandt, Eva, Clark, Brendon and Binder, Thomas (2011). Rehearsing the Future, Copenhagen: The Danish Design School Press.

IPCC (The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. <http://www.ipcc.ch/, Accessed on Dec. 2, 2014.>

Simonsen, Jesper and Robertson, Toni (2013). The Routledge Handbook of Participatory Design, New York, NY: Routledge.

Wiman, Veronica (2014). ‘Approaching Urban Gardening/Farming: Initiatives by Citizens, Municipalities, and Governments’, Podium, vol. 8, Universitetet i Tromsø, Det kunstfaglige fakultet.