For the last five years, Jacek Smolicki has on a daily basis been recording the everyday sounds of the places he has been at. Being interested in so-called life-logging and self-tracking practices, he recently started using a small camera that snaps a photo every 30 seconds. “Looking at these photos”, he writes, “is like looking not at my life as I experience it but rather my parallel life”. In the record, random people whose presence he didn’t even notice suddenly become central figures.

Unintended Memories and Parallel Spaces

Text: Jacek Smolicki, PhD student in the Living Archives project.

As one part of my PhD thesis I look at life-logging practices, inquiring whether we can talk about them as contemporary forms of personal archiving. Generally speaking, life-logging is a practice of incorporating some media device (e.g. mobile phone, GPS device, a portable or wearable camera) to record and store an extensive amount of audio, visual or biophysical data representing one’s everyday life.

Interested in various spatio-temporal entanglements of people and recording technologies, besides analysing what a particular incorporation of a recording and tracking media device into one’s life communicate and represent, I also explore what kind of impact it causes on the very subject and his/her daily life. As a part of the study I also look at a set of self-initiated practices of documenting my life that I have been performing ever since 2009. Lately, exploring what I refer to as passive self-tracking, I purchased a wearable device called Narrative Clip – a small wearable camera set up to automatically take one snapshot every 30 seconds. One typically attaches it to a shirt or a jacket letting it ‘seamlessly’ take pictures and compose them into a chronological sequence depicting one’s particular experience, journey or an entire day.

Hereby, after wearing the camera continuously for the last 18 days, I would like to share some of the initial observations along with a selection of photographs. My intention is to keep wearing the device for a course of this year and while performing my other, active forms of documenting my presence, compare these two and discuss implications that both involuntarily (passively) and voluntarily (actively) enacted archiving practices have in relation to my everyday life and the space I occupy at the time.

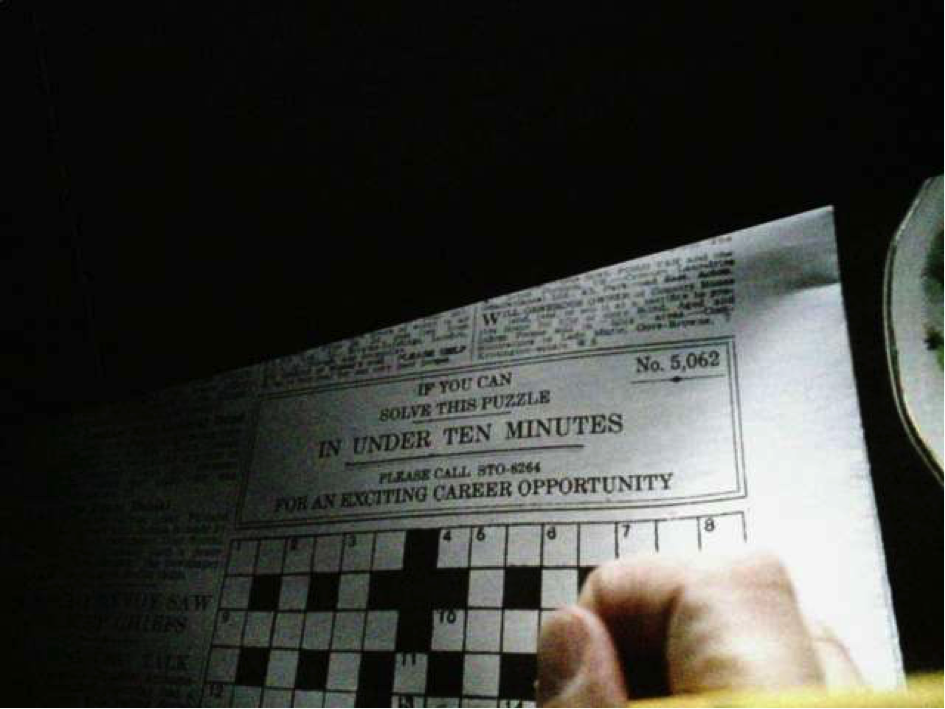

Figure 1. One of the pictures of me reflected in a mirror and depicting Narrative Clip as attached to my sweater.

Observation 1 – gestures and movements are co-choreographed by the device

During the first day (Birmingham airport, London, January 1) of wearing the camera, which I attached to my jacket at the chest level, I remained almost all the time aware of it. Although none of my interlocutors noticed the device, approaching someone face to face (e.g a train service person, a ticket seller) made me feel rather embarrassed. Even though I was in the public space, I was aware that I might be violating people’s privacy. During the first day and on the few following ones, I realized that being aware of the camera attached to my body to some extent choreographs my movements. For instance, when talking to someone face to face without having a chance to point at and explain why I wear the camera, I would twist my body, to make sure that the person’s face does not become captured. However, as a result of intentionally shifting the angle, I would get a sequence of photographs depicting spaces or situations I was not necessarily paying attention to at the moment. In fact, while attempting to avoid capturing one person’s face by changing the direction of the lens, I would accidentally end up capturing other people. An intentional decision of changing the angle would result in a series of unintended images, creating somewhat an unintended memory trace. Random people whose presence I did not even notice, in the record suddenly become central figures.

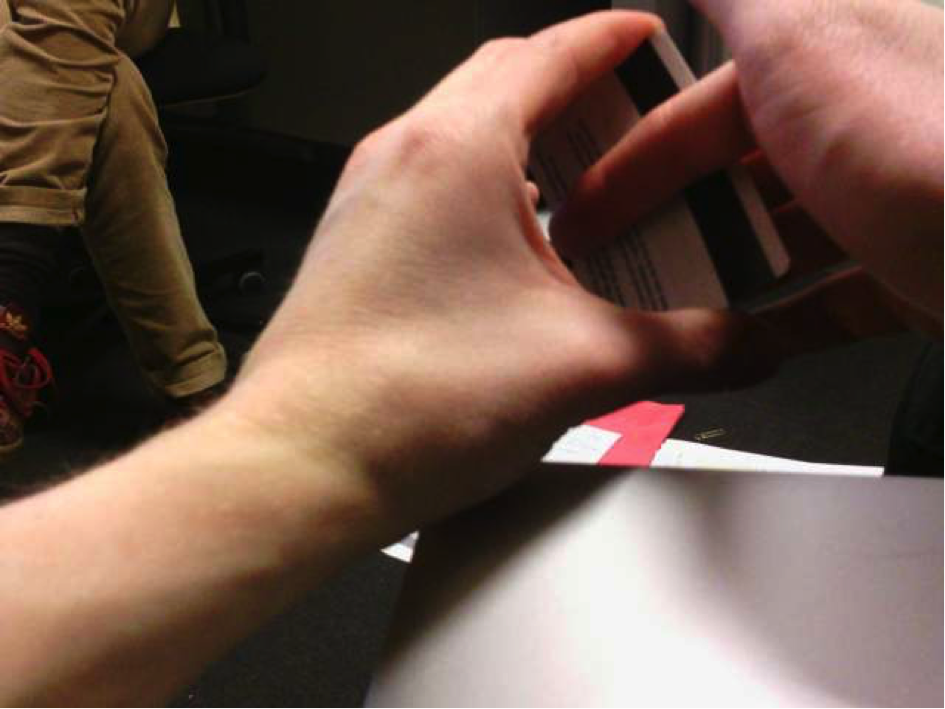

Figure 2. Purchasing a ticket to the exhibition at Tate Modern in London and making sure that the camera does not depict the face of the person unaware of me wearing the device.

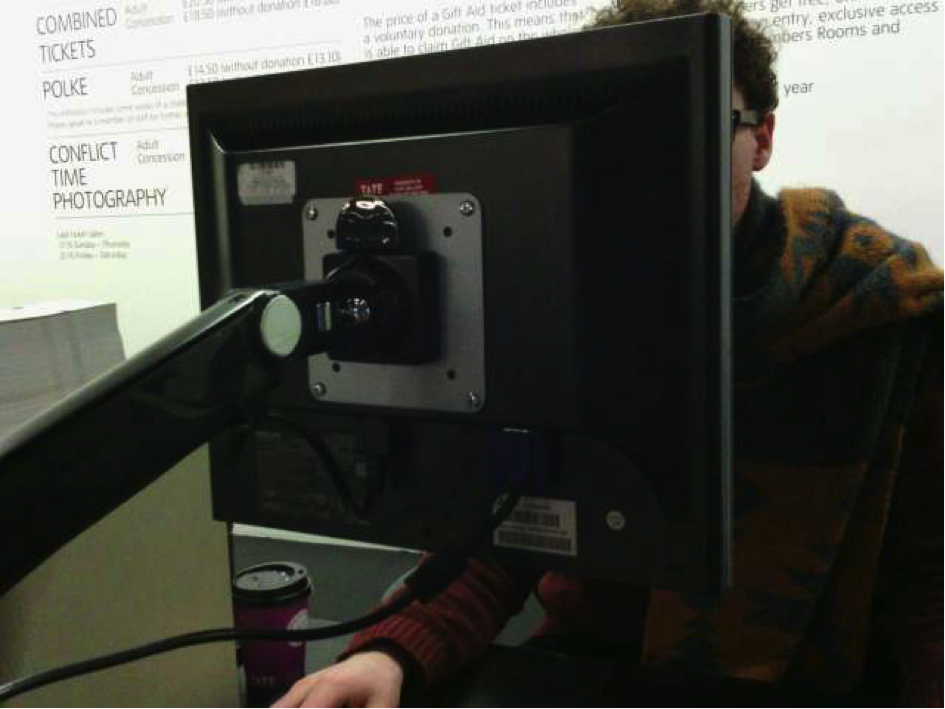

Figure 3. At the exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography at Tate Modern in London – one of the first experiences recorded on the wearable camera when visiting the UK for the New Year’s. Reflecting on the record of my visit let me not only return to some artworks I was drawn to but actually see which of them especially kept my attention for a longer period. In this case the interval-based capturing of the experience might facilitate some useful observations.

If finding a particular place or situation interesting I would remain there still for at least 30 seconds to make sure that the place becomes a part of the log (even though the camera can take pictures if tapped two times, I do not want to use this function too frequently, as my goal is to do my best to forget about the camera’s persistent presence and let it act automatically).

Figure 4. Making sure that the unusual perspective is recorded by remaining at the place for at least 30 seconds. At the St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Observation 2 – many encounters are influenced by the project framework

The Narrative Clip affected not only my movements, but also subjects and dynamics of the conversations with people I met and to whom I introduced the device and the idea behind the project. The need to explain the reason for wearing the camera determined every conversation, or at least its beginning. Thus, every encounter with a person with whom I speak about the project is partially a construction of the very project. The need of introducing the project constitutes a sort of a ritual that precedes and informs every interaction.

Figure 5. A random person in the background, as a consequence of the slightly tilted angle of the camera, becoming a central figure in the picture and the whole sequence.

Observation 3 – how the camera ‘sees’ is a little bit accidental

The camera is designed to be worn on clothes (e.g. a collar, pocket, etc.), not directly on the body. Therefore, the angles of the photographs are easily subjected to the rumpling of the clothes. While I remain looking straight ahead, affected by the arrangement of my clothes the camera might be depicting a situation taking place aside of my scope (see figure 5)

Observation 4 – long and static situations have priority

Analysing sequences of photographs makes me feel like my days are spent predominantly on waiting at bus terminals, sitting on buses or generally remaining passive. Since pictures are being taken every 30 seconds, my remaining in a static position has a better chance to be depicted than the short moments of a dynamic movement and spontaneous, transient gestures. While usually it is the latter type of a situation that I would memorize (for instance rushing to school on a bicycle or bending my body while laughing) the time-based method of recording and rhythmicizing the log prioritizes long, static situations and saturates their visibility presenting them as major events during the day at the cost of more ephemeral, sudden situations (see figure 7).

Figure 6. One and a half hours of a beginning of a day. The most static situations dominate the sequence.

Observation 5 – like looking at a parallel life

Looking at the lifelog as being organized by the software that comes with the wearable camera makes me feel as if I were looking not at my life as I experience it but rather my parallel life, happening right aside. Or perhaps, to put it better, in a parallel space that I found myself in but which I did not experience directly, consciously.

Figure 8. This picture, (having more affective quality due to the blurriness and a tilted angle), upon going through the daily log of images succeeded to reconnect with a particular memory attached to it. A couple of minutes before it was taken, having found a credit card in front of a grocery store I walked in, rather fast, and approached one of the staff members in order to report the finding.